Proposals to restrict motorcycles were first raised in 2017, yet it was not until July 12, 2025, that the Prime Minister Phạm Minh Chính issued an urgent directive to implement this policy. Following that, on Sept. 30, 2025, the Hà Nội People’s Committee issued Plan 267/KH-UBND to carry out Directive 20/CT-TTg, which mandates the creation of a roadmap to phase out gasoline-powered motorcycles. Despite this long delay, the language surrounding its implementation is now filled with phrases like “urgent,” “pressing,” and “accelerate.”

This sudden rush is colliding with a fast-approaching deadline. Starting July 1, 2026, the ban on gasoline motorcycles within Hà Nội’s Ring Road 1 will take effect, a move expected to directly affect approximately 450,000 vehicles.

Both residents and experts have expressed concerns about the feasibility of Directive 20. Numerous questions remain about Hà Nội’s public transportation system, alongside heated debates over the transition to electric vehicles—specifically regarding power supply infrastructure, charging stations, battery fire prevention, and home charging equipment. These factors indicate that no one is truly ready for such a sudden, wide-ranging change.

Nevertheless, authorities show no signs of slowing down and are rushing to implement measures like installing charging stations and assisting residents with vehicle transitions. This highlights a painful problem: authorities are only beginning preparations when the deadline is imminent, leaving the public no time to prepare.

Unfortunately, this situation is not new.

“Virtual” Policies and the Erosion of Legal Effectiveness

The pattern of laws and policies being enacted before the capacity to implement them is ready has become a chronic issue in Việt Nam. Over the past year alone, numerous laws affecting citizens directly have been issued hastily and without careful preparation.

Beyond Directive 20, the issuance of Decree 168/2024/NĐ-CP provides another clear example. This decree, which directly affects citizens’ rights, was enforced so rapidly that two weeks after it took effect, traffic in both Hà Nội and Hồ Chí Minh City became increasingly chaotic.

Only after public backlash over high fines while infrastructure remained underdeveloped did authorities scramble to overhaul that infrastructure overnight. Similarly, Decree 70/2025/NĐ-CP, which abolished fixed taxes, and new policies on tax declarations were also issued hastily, leaving citizens confused.

This “run-and-arrange” approach extends deep into the state itself. The massive reorganization of Việt Nam’s political system—shifting from vertical to horizontal structures, from central to local levels—was implemented in a rush. This has caused operational problems, obstacles in administrative procedures, and disruptions to the lives of government officials and citizens alike.

In a system praised as “streamlined, lean, strong,” confusion is evident: deputy chairpersons of commune-level People’s Committees may have to sign thousands of notarized documents in a single day, or leaders may be relegated to bureaucratic tasks with no precedent.

This period of reorganization was facilitated by equally hasty legal changes. The Constitution was amended in just 43 days, and other major laws were revised to facilitate the administrative reform.

This led to the paradoxical situation of the National Assembly passing the 2025 Law on Local Government Organization No. 72/2025/QH15, only to replace it with Law No. 65/2025/QH15 a few months later. Notably, these amendments were merely the final steps to legitimize what had already occurred.

A common feature of these policies is the lack of thorough research, insufficient attention to impact assessment, and weak consideration of practical implementation. The results are predictable: documents require continuous amendments, planning begins only as deadlines approach, and the state only addresses problems after they have been exposed.

Ideally, the legal system should provide a stable, long-term framework. Yet in Việt Nam, laws are often treated as “trial versions.” A policy is issued, and society is left to cope. This cycle—rapid issuance, problems, fixes, further problems—traps the system in a perpetual loop, eroding legal effectiveness, diminishing public trust, and rendering policies infeasible.

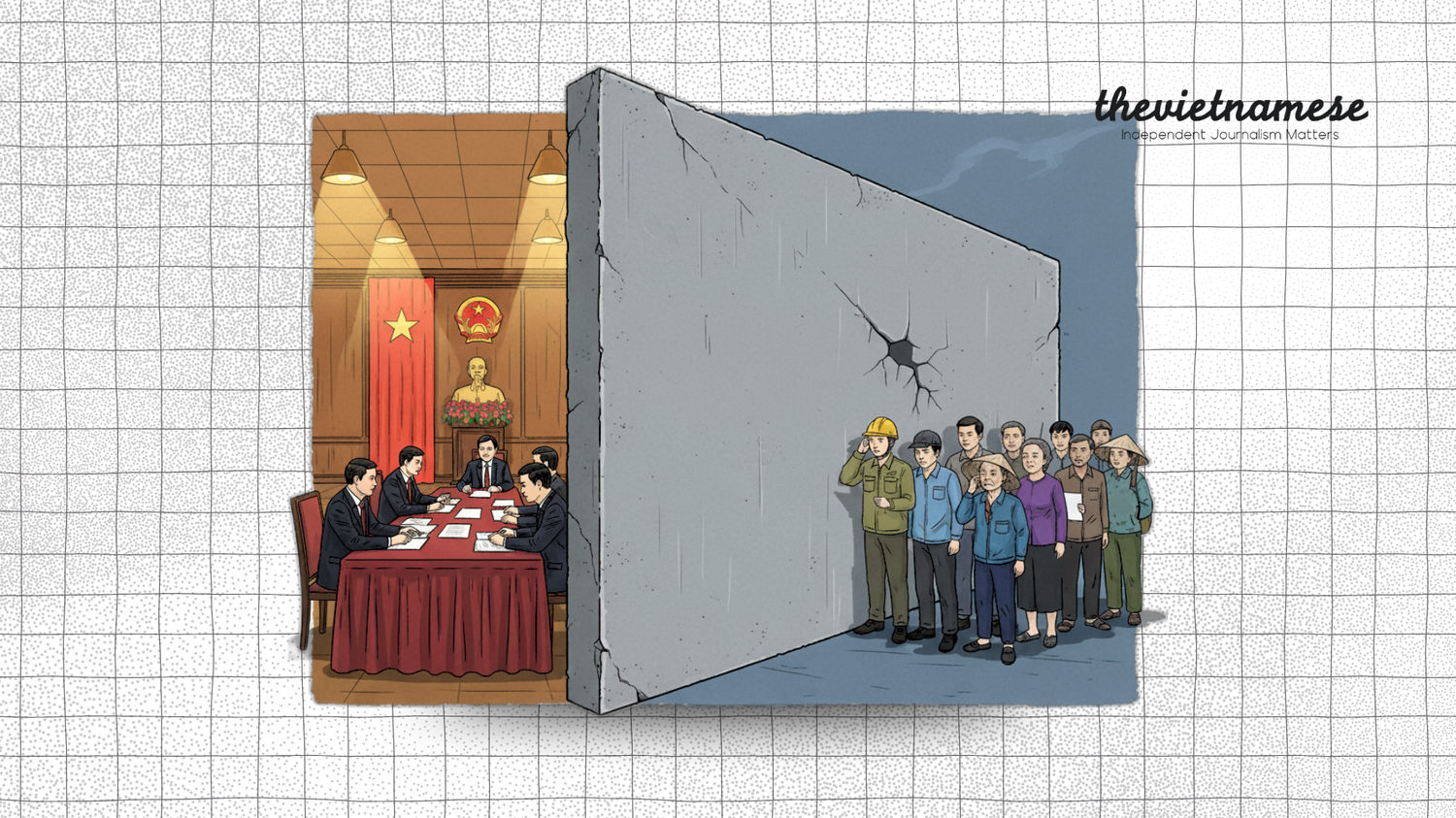

The Increasing Alienation of Citizens from Legislative and Policy Processes

In this “run-and-arrange” approach to lawmaking, authorities appear to have overlooked the public’s voice and the constitutional rights of citizens to ownership and oversight. Soliciting public opinion is a fundamental step, as citizens are the ones who must implement and be affected by new regulations. In practice, however, law and policy development in Việt Nam often does the opposite.

According to the amended Law on the Promulgation of Legal Documents, the minimum time for public consultation has been reduced to less than a third of the previous duration. For normal procedures, the time is now only 20 days; for expedited procedures, just three. In special cases, citizens have no opportunity to provide input at all.

Recently, the National Assembly and citizens were even excluded from the constitutional amendment process. Many other legal documents were issued hastily under abbreviated procedures, lacking genuine social consultation or relying on perfunctory surveys.

This has widened the gap between “actual citizen opinion” and “officially published citizen opinion,” a divide exemplified by the public backlash to Directive 20 and Decree 168. Witnessing these continuous cycles of issuance, amendment, suspension, and problem-solving has fostered public skepticism about the law’s effectiveness and the state’s capacity.

Furthermore, citizens cannot keep pace as documents are issued, amended, and supplemented continuously. Gradually, the public loses meaningful participation and is excluded from the legislative process. In a regime still claiming the principle of “democracy,” the consequences of repeatedly sidelining the “sovereign” are predictable.

Is the “Party’s Will” a Prerequisite for Lawmaking and Policy?

The phrase “ý đảng, lòng dân” (“the party’s will, the people’s heart”) appears frequently in speeches by Việt Nam’s leaders, with state media praising their harmony. But is this true in practice?

Many laws and policies do not align with public sentiment, and the public has little chance to express it. Yet these documents are issued “correctly” according to the party’s will.

Even the National Assembly—the representative body of the people—must maintain and enhance party alignment. Legislative activity is thus not independent but primarily implements the party’s directives, with a Politburo resolution immediately becoming a “guiding compass.”

Historically, policy-making has adhered to the principle of “ensuring comprehensive and direct leadership of the Communist Party of Việt Nam.” Once the “party’s will” is decided, almost no one dares question if conditions are sufficient, resources are ready, or if citizens will accept it. Law becomes a tool to legitimize directives rather than the outcome of deliberation.

The statement “the party’s will and the people’s heart are harmonious” may only be true if one equates the two. In other words, the “people’s heart” as an independent factor exists only faintly once the “party’s will” becomes a command.

This “political command” turns lawmaking into a race against time, explaining why many documents are symbolic: decisive on paper but awkward in execution, such as “streamlined machinery” or “provincial mergers.”

Policy often functions more as a declaration of determination than as a feasible solution. In a system where law is subordinate to party directives, the legislative process inevitably prioritizes political will over practical reality. The consequence is that laws do not originate from real conditions, and when they collide with reality, their inconsistencies emerge. These inconsistencies will persist as long as authorities continue to take pride in the “run-and-arrange” approach to governance.

Trường An wrote this article in Vietnamese and published it in Luật Khoa Magazine on Oct. 13, 2025. Đàm Vĩnh Hằng translated it into English for The Vietnamese Magazine.