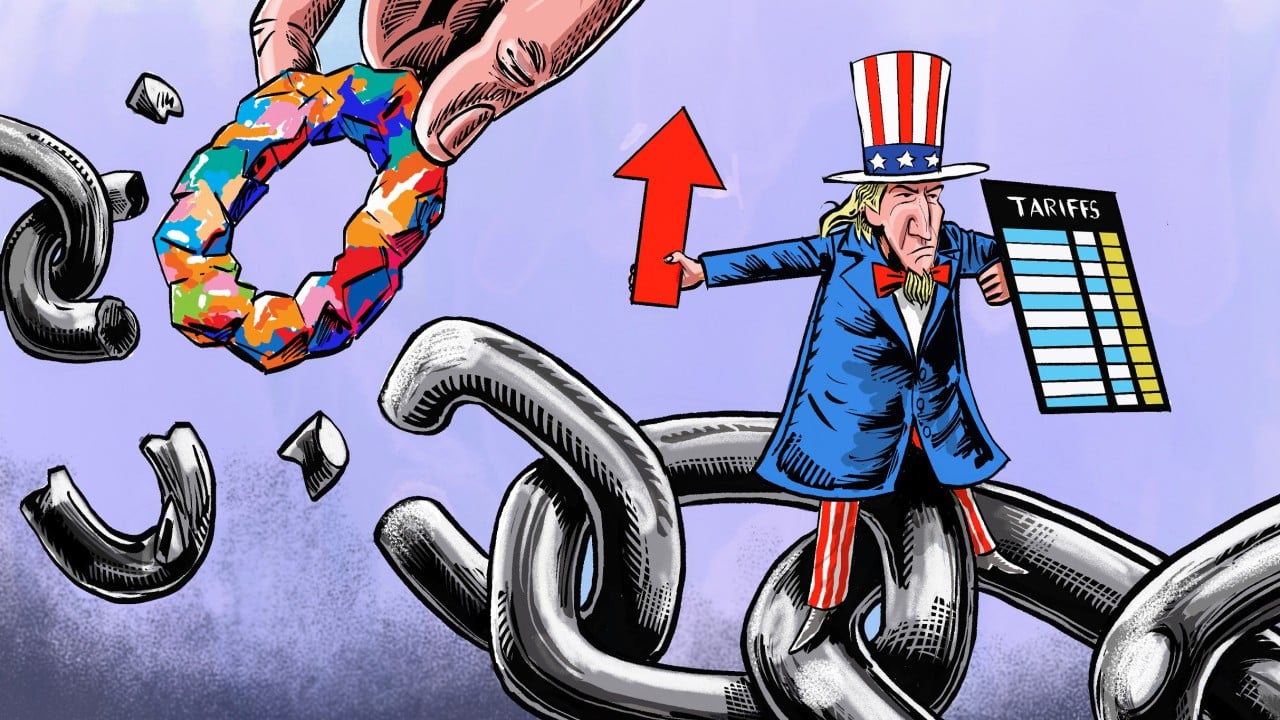

US President Donald Trump has returned to a trademark policy in announcing a new round of trade confrontation that clearly echoes the conflict he launched in his first term. Officially, the trade war began on January 22, 2018, when he imposed a 30 per cent import tariff on solar panels.

Advertisement

While such measures are usually justified by noble intentions – protecting domestic industries and reviving local manufacturing – in reality, trade wars are often driven by the desire to seize foreign markets and weaken rival economies. But Washington had already missed the moment to contain Beijing’s rise.

Between 1990 and 2018, China’s share of global gross domestic product in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms grew from 3.8 per cent to 17.3 per cent, while the US share fell from 20.1 per cent to 15.6 per cent.

The trade war launched in 2018 and subsequent rounds were essentially an attempt to “restore fairness” and reclaim America’s economic leadership. But has this strategy succeeded? According to the data, not really – China’s share of global GDP in PPP terms has since risen further, to 19.3 per cent, while the US share has slipped to 14.8 per cent.

Economic research on trade wars shows they harm all participants, leading to a decline in global performance indicators. Yet, in most cases, larger economies tend to fare better and nations with more diversified economic structures are generally less vulnerable to external shocks.

Advertisement

Given the tight interdependence of today’s economies through global supply chains and growing trade, pressure on any key player inevitably affects everyone else. The question is how strong the multiplier effect will be. Our 2018 simulations indicated that China would suffer less than the US, as it could redirect much of its exports and replace missing imports with alternative suppliers – a scenario that proved largely accurate.