On April 30, 1975, after only 20 years of existence, the sole democracy in the history of Vietnam came to an end amidst a Communist takeover. It remains the only democratic period because, throughout its millennia of history, Vietnam was either under an absolute monarchy or under foreign domination, and for the past half-century, a one-party dictatorship.

Despite the difficulty of building a new nation after 100 years of French colonial rule while defending itself against Communism, the Republic of Vietnam (RVN) – South Vietnam (SVN) achieved remarkable results across politics, economics, society, and culture.

The most significant of these were in education, the arts, and literature. The richness of southern literature can be measured by the published materials preserved in the U.S. Library of Congress, American universities, and, for the past two decades, on the internet, thanks to individual efforts.

Southern literature survived despite a persecution campaign of book-burning and the arrest and imprisonment of independent writers after the North Vietnamese Communists (NVC) took over the South in 1975. Not only did it survive, it was also revived, becoming a source of inspiration for Vietnam’s next generations, both overseas and within the country. Perhaps no other literature in the world has been able to achieve lasting results in such a short amount of time.

The development and achievements of Southern literature from 1954 to 1975 mark one of Vietnam’s two most vibrant and rich literary periods, rivaled only by its pre-war counterpart, văn học tiền chiến (pre-war literature) (1930-1945). First-hand witness accounts reveal how the NVC persecuted Southern literature, imprisoned its writers and artists, and how it was revived by the Vietnamese exile community after 1975.

20 Years of Literary Development Despite the War

Following the Geneva Accords of 1954, Vietnam was divided into two parts. The North fell into the orbit of Communism, leading to the mass migration of nearly a million people to the South. There, with the assistance of the United States and the free world, a new nation founded on the principles of liberal democracy was born: the Republic of Vietnam (RVN).

The Northern immigrants, known as Bắc kỳ Di cư, who escaped to the South brought with them the entirety of văn học tiền chiến—pre-war literature that had been suppressed by the communists. Together with their Southern colleagues, these immigrating writers and artists also helped preserve the works of the Nhân Văn Giai Phẩm (Humanism Periodical) group.

The Nhân Văn Giai Phẩm group had briefly emerged in the North in the mid-1950s when artists and writers demanded freedom of creation but were brutally suppressed by the NVC government. Their works clandestinely “crossed the border” to the South and were later curated by scholar Hoàng Văn Chí in the anthology, Trăm hoa đua nở trên đất Bắc (Hundreds of Flowers Blooming in the North).

In her essay, “Văn học miền Nam (Southern Literature),” critic Thụy Khuê points to three factors behind the vibrant and colorful development of Southern literature within a mere 20 years:

“The South […] has a long-standing national language [chữ Quốc ngữ] tradition, and the Southern language itself is a diverse, colorful, and rich source of language for immigrating Northern writers; many have relied on this new treasure to enrich their literary language. This was due to three factors:

1. Based on the national language foundation from the end of the 19th century, plus the Southern language as a new linguistic treasure,

2. Thanks to the preservation of pre-war literature and the preservation of Nhân Văn Giai Phẩm during the period of national division, the South was not cut off from the literary past and present of the country.

3. Thanks to the connection with foreign literary and ideological trends.

As a result, the South was able to build diverse literature in the context of war and political instability.”

These factors formed the foundation on which Southern literature was built and flourished. This literary development was also strongly supported by the RVN education system, which was based on the core principles of humanism, nationalism and liberalism.

What is an education based on humanism, nationalism, and liberalism?

Professor Lê Xuân Khoa was a witness to the history of education in the RVN before 1975. As the deputy minister of education of the RVN, he took part in the 1956 National Education Conference that led to the establishment of the South’s educational philosophy. This conference took place just one year after the French government granted full independence to the RVN government, giving birth to the Republic. In a discussion on Radio Free Asia (RFA), he said:

“Humanism is about people, taking people as the basis of salvation. Therefore, education must focus on people and developing a complete person, a person with universal human values. While talking about personality on such a human basis, there must still be the Vietnamese character, which is [our] national character. Raising a child from childhood to adulthood to become an intellectual that has a human basis and a Vietnamese basis to contribute to the human community. That is our national character.

And third is the issue of openness, focusing more on science. Because Vietnam is in the context of being an underdeveloped country […], so openness to opening the door to receive all the best things, especially in the world of science and technology, mostly from the West. Receiving like that, there is a foundation of humanism, the characteristics of the Vietnamese people and receiving the advanced science of the West, then such a person is a complete person.”

It was this educational philosophy that nurtured those who grew up during the Republican era, creating a new generation of young writers who were imbued not only with the fruits of pre-war literature but also with classical Vietnamese works embedded in humanity, propriety, wisdom and trust, in addition to the translated literary and philosophical works by international authors.

From a practical perspective, such education has also created a much-needed community of readers. In turn, this readership sustained the publishing industry, supporting textbook authors and creative writers alike.

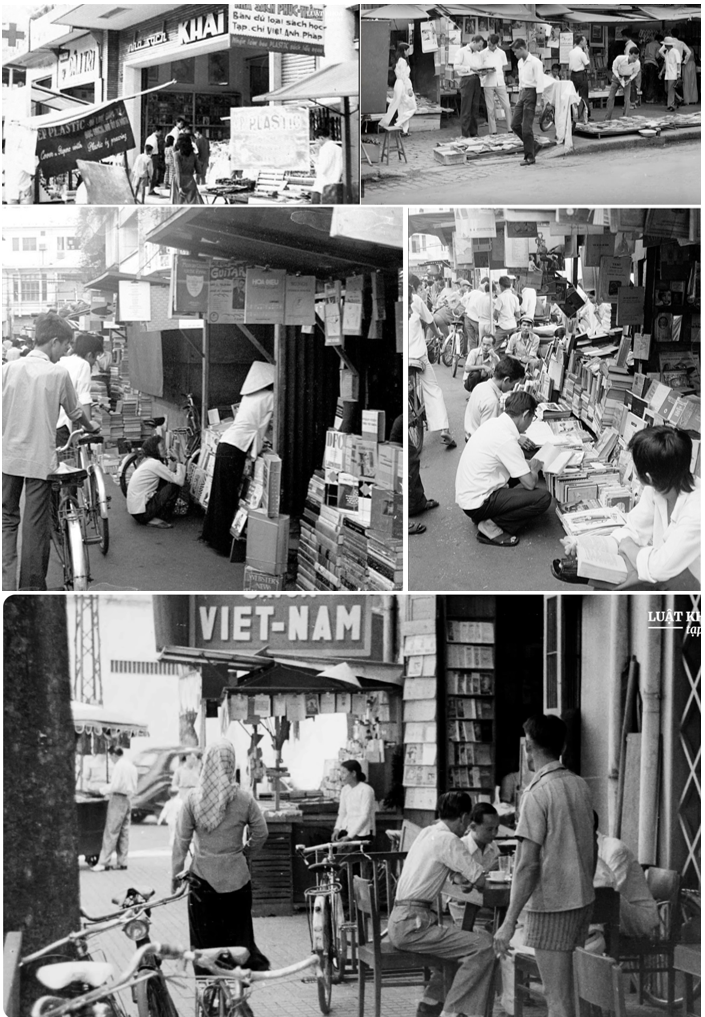

With such a vast demand from a growing readership, the supply side of the publishing industry naturally flourished. According to a short but concise documentary on YouTube by Luật Khoa Magazine, by 1975, South Vietnam had approximately 900 printing houses and 180 publishing houses—compared to the 21 houses present in the North.

This infrastructure supported the publication of more than 1,000 titles each year. The writer Đoàn Thêm, author of the multi-volume series Chuyện từng ngày (Stories of Everyday), noted that from 1961 to 1963 alone, 2,624 titles were published, with novels and poems making up a significant portion (546 titles). In 1965, 1970 and 1973, a total of 96,000 tons of paper was imported for more than 700 printing houses, which collectively produced 86 million books.

While many of these were textbooks, the sheer volume of this industry led to the development of a vibrant literary life. Before 1975, many writers in the South were able to make a living entirely from their craft. More specifically, there were women who had previously never dared to think that they could make a living by writing, let alone by publishing novels.

This led to a remarkable social phenomenon: the emergence of professional female writers who supported themselves and their families through writing. Notable examples include Bà Tùng Long, Nhã Ca, Túy Hồng, Nguyễn Thị Hoàng and Nguyễn Thị Thụy Vũ. This topic is explored further in the article, “Phụ nữ viết văn thời Cộng hòa” (Women Writers in the Republican era), available here.

The writer Võ Phiến recorded the literary activities of the South in vivid detail through the first volume of his work, An Overview of Southern Literature. This seven-volume series was first published in California by Văn Nghệ Publishing House in 1986 and in 2000 with updated appendices, including one on the Communist book burning campaign.

In the Tác giả and Tác phẩm (Authors and Their Works) appendix, Võ Phiến listed about 350 writers and some of their published works. A large number of these individuals belonged to the generation that matured after 1954, but the list also included other writers from the pre-1954 migration. These veteran authors often became more productive in the South’s open atmosphere and due to high reader demand, rendering Southern literature more vibrant, rich, and diverse in both volume and depth.

However, this literary flourishing occurred against the backdrop of an escalating war. In the early 1960s, the NVC launched a campaign to invade South Vietnam through the National Liberation Front, which culminated in the 1968 Tết Offensive. The attacks on several populated cities shocked the Southerners since both sides had agreed to a three-day ceasefire to celebrate the Lunar New Year holiday. Many neighborhoods in Sài Gòn were destroyed.

According to witnesses in Huế, thousands of innocent people were massacred and thrown into mass graves, some reportedly while still moving and breathing. The war continued even after the signing of the 1973 Paris Peace Accords. The North sent hundreds of tanks across the Demilitarized Zone at Bến Hải to attack Quảng Trị and threaten Huế, while opening new fronts in Bình Long and An Lộc. Soldiers and civilians from both sides died en masse.

This NVC offensive resulted in the massacre of about 2,000 refugees when Communist artillery from the Trường Sơn mountain range rained down on Highway 1 in the Mỹ Chánh area. For months, the bodies of civilians, including women and children, remained scattered on both sides of the highway, as ongoing fighting prevented relatives from collecting them for burial.

When the Sóng Thần newspaper launched a fundraiser for the collection and burial of these war victims, their staff witnessed firsthand the decomposed bodies on this stretch of the road nicknamed, “The Highway of Horror” (Đại lộ Kinh hoàng.)

Please see the report and related documents (in Vietnamese) here. Professor Vân Nguyễn-Marshall of Trent University, Canada, has also written a comprehensive paper on the Sóng Thần campaign, titled “Appeasing the Spirits Along the ‘Highway of Horror’: Civic Life in Wartime Republic of Vietnam, War & Society,” at this link.

Despite the war, death, and destruction, Southern writers and artists operated with a creative freedom that allowed them to spontaneously and truthfully express their thoughts, feelings and aspirations; they were not told what or how to write.

This produced an era of art that reflected the painful reality of the time, with titles like Đêm nghe tiếng đại bác (Listening to cannons at night), Em hỏi anh bao giờ trở lại (You ask me when I may return), and Ngày mai đi nhận xác chồng (Tomorrow I’ll go and receive my husband’s body).

The response to the war was varied; some works were explicitly anti-war or captured deep societal grief, while others expressed a longing for peace, such as Nối vòng tay lớn (Join Hands to Create a Large Circle), or even escapism, as in Lên non tìm động hoa vàng (Heading to the Mountain in Search of a Yellow Flower-Filled Cave). The result was a literary landscape as wide and diverse as a thriving field of wildflowers.

During an online discussion a few years ago, a young participant asked for my perspective on this period.

She wondered if Southern literature, being mostly sentimental and sad, was partly responsible for the collapse of the South? I replied that it might be one of the countless reasons that led to the RVN’s disintegration.

She then asked if writers should have avoided creating such pessimistic or sentimental work. I replied that no one could betray their true feelings, and that perhaps, this was the price one had to pay for telling the truth. The young woman, who was born and grew up in Hanoi, later emailed me to say that my answers had moved her to tears.

The Campaign to Destroy Southern Literature

Perhaps one of the most compelling accounts of the post-1975 campaign to eliminate Southern culture comes from the famed scholar Nguyễn Hiến Lê, who became a direct witness after deciding to stay in Vietnam due to his sympathies for the Communist cause.

He documented these events in Hồi Kí, Tập III (Memoirs, Volume III), of the three-volume series published by Văn Nghệ Publishing House in 1988; it is the only edition faithful to the original manuscript that the author secretly sent overseas for publication. On pages 74-80, he described the campaign to burn and confiscate books in the South, as excerpted here in the following account:

“One of the first tasks of the [new] government was to destroy all publications (books, newspapers, and magazines) of the puppet Ministry of Culture, including translations of works [in Chinese] by Lê Quí Đôn, poems by Cao Bá Quát and Nguyễn Du; French, Chinese, and English dictionaries were also burned. In 1976, a deputy minister of culture from the North came to see this and expressed regret.

But did that deputy minister know the government’s policy, because in 1978, the Northern government not only approved of the book destruction but also considered [the campaign] not thorough enough, and ordered the destruction of all books in the South, except for books on natural sciences, technology, and dictionaries; thus, not only novels, history, geography, law, economics, but also poems and literature written by our ancestors in Chinese characters, later translated into Vietnamese, and even the works of Kiều (The Tale of Kiều), Chinh Phụ Ngâm (Lament of the Soldier’s Wife)… printed in the South must all be destroyed.

In 1975, the Department of Information and Culture of Hồ Chí Min City forced publishers to submit two or three copies of any books they still had in stock for censorship: after several months of work, they compiled a list of dozens of reactionary or decadent authors and hundreds of banned works, while the rest of the books were allowed to circulate. But those were only the books still in the publishing houses; there were many out-of-print books in private homes, so how could they be censored?

Therefore, the Department of Information and Culture issued a directive to each district to send youths to reactionary and decadent books in each home to bring back and burn. Most of those youths did not know foreign languages, and they rarely read Vietnamese books, so of course, they would do something wrong.

They went into every house, picked up any French or English books they saw, and collected all the Vietnamese novels, regardless of content. They couldn’t go into every house, so they went into any house where they didn’t like the owners, or the police would point out a house… At that time, quite a few books were burned in Sài Gòn. It was said that all kinds of obscenities and martial arts books filled the room of a district information chief, and a few years later, he called someone to sell them at a high price.”

Nguyễn Hiến Lê, a respectable and credible writer who had lived through the book-burning campaign by the Communist regime, continued to remark:

“The second time [of book-burning] in 1978 caused a stir in public opinion. In accordance with the directive of ‘three destructions,’ only natural science books could be kept, and the rest had to be destroyed, because if they were not reactionary (one destruction), they were also depraved (two destructions), if they were not reactionary, depraved, they were backward (three destructions), and each family could only keep a few books, at most a few dozen dictionaries, math, physics… Everyone was confused, and they met with each other and asked what could be done. There were days when I had to meet five or six friends to ask for advice.”

Lê added:

“Not only did the communist government confiscate and burn Southern literature books, it also arrested and imprisoned about 30 famous writers of the South, whom they called ‘spies,’ ‘counter-revolutionary propagandists,’ and ‘literary commandos.’”

The new government ordered the remaining artists to attend “Political Training for Artists in the South” courses, each lasting several months. Meanwhile, a propaganda campaign was launched, with dozens of books written by Communist writers and their previously undercover agents.

These works denounced Southern artists and used titles such as “Neo-colonialist commandos on the cultural and ideological front.” These artists were branded criminals against the people and lackeys of American neo-colonialists who wrote and disseminated “slave culture, depravity, hybridity, and extremism” to poison the people.

In his comprehensive 1,600-page series, Văn học Miền Nam (Southern Literature) 1954-1975, author Nguyễn Vy Khanh documents this campaign. He notes that from 1975 to 1979, nearly 20 books were published that criticized the Republic era’s literature and arts as “literature that is a lackey but as scary as bombs!” In an article taken from the series, he writes:

“In March 1981, the Hanoi authorities issued a new list of 122 authors whose entire works were banned from circulation. In this campaign of condemnation and suppression, according to official statistics, in the third phase of the campaign in June 1981, the Communist government confiscated 3 million publications nationwide, of which 316,314 were banned books and newspapers; in Saigon alone, 60 tons of books (151,200 copies), 41,723 music tapes, 53,751 paintings, 631 films, etc. At the same time, 205 secret printing houses were discovered (according to Trần Thọ, Communist Magazine, October 1981).”

With so many efforts to eradicate free Southern literature, what has become of it?

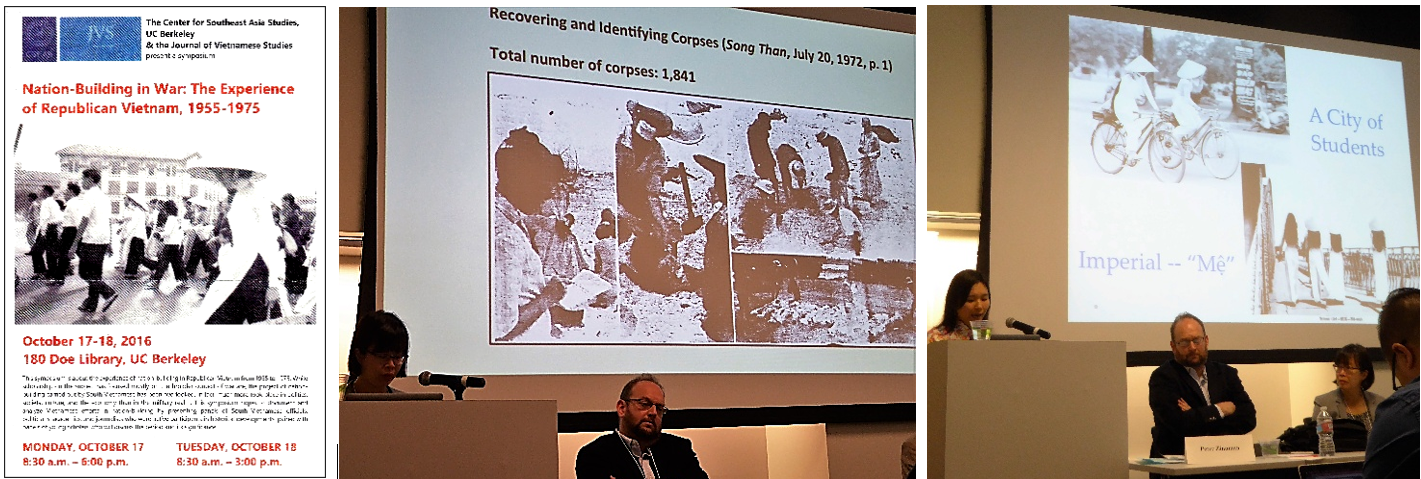

A prominent Southern writer at that time predicted its fate. Nhã Ca, the author of Đêm nghe tiếng đại bác (At Night I Hear Cannons) and Giải khăn sô cho Huế (Mourning Headband for Huế), shared her firsthand account at a conference on the Republic of Vietnam’s wartime nation-building efforts, held at the University of California, Berkeley in late 2016:

“It was a spring afternoon, at a three-way intersection in the Chu Mạnh Trinh residential area in Phú Nhuận, there was a scene of the local police mobilizing young people to burn books. The place where the books were burned was the street right next to the home of the prominent writer Nguyễn Mạnh Côn.

Standing with us on the balcony of the first floor, looking down at the book burning scene, Côn said while smiling, ‘You guys shall see. The words of Southern writers, the songs of Southern artists, you can burn them until the Tết Congo[meaning “never taking place” like a Tết to happen in Congo]but it won’t make any difference.’ Just a week later, there was an unprecedented police operation. On the night of April 3, 1976, hundreds of Saigon writers and artists were arrested. Côn, us, both husband and wife, were all imprisoned and later exiled.”

Nhã Ca was imprisoned for two years and later released to take care of her young children while her husband, poet and journalist Trần Dạ Từ, was imprisoned for 12 years. She continued to talk about the time she was detained at a concentration camp for artists in Gia Định, a suburb of Saigon:

“Once, a group of prisoners of literature and arts were herded into a car and taken to the ‘American-Puppet Crime Exhibition House’ to ‘study.’ The exhibition area was an old university lecture hall, and the crimes displayed were books from Southern literature. Among them was my book. The book Giải khăn tang cho Huế (Mourning Headband for Hue: An Account of the Battle for Hue, Vietnam 1968″ was hung high. All of us prisoners of literature stood at attention. Looking straight ahead. Quietly. Respectfully saluting our works and our friends.

The cultural power of Saigon’s books and newspapers can truly awaken those who have been deceived, wrote a Northern female writer who had come to liberate the South. […] On the first day of ‘liberating Saigon,’ as soon as she saw the books from the South, she cried because she then understood that she had been deceived, that many generations had been deceived. I believe what she wrote. Like the people, like the streets, fields, and gardens, Southern culture, literature and art are achievements that have appeared right in the midst of collapse. And that becomes clearer and clearer. There is no way to erase them.”

The humanistic literature of the South left a profound impact, mesmerizing not only Dương Thu Hương—who would later gain fame for her novel Thiên đường mù (Paradise of the Blind)—but also many of her comrades.

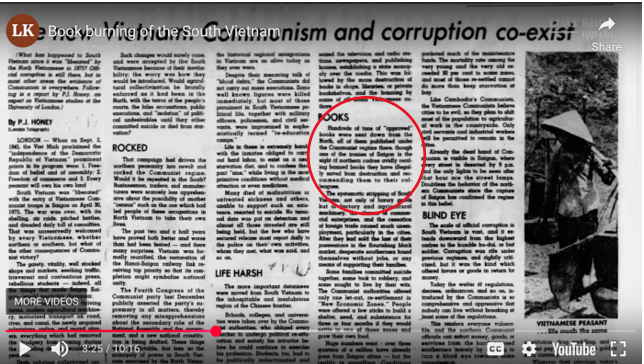

Patrick James Honey, a British scholar fluent in Vietnamese and an expert on Vietnam, commented on this cultural suppression.

In an article for the London Telegraph titled, “The New Vietnam: Communism and Corruption Co-exist,” published during this period of eradication, he wrote: “Hundreds of tons of ‘approved’ books were sent down from the North, all of them published under the Communist regime, though one of the ironies of Saigon is the sight of northern cadres avidly reading banned books they have illegally saved from destruction and recommending them to their colleagues.”

In essence, Southern literature infiltrated the hearts of the generation that came to liberate the South. These soldiers themselves were the ones being liberated from a lifetime of brainwashing propaganda.

It is not surprising that in the mid-1980s, faced with a devastating economic crisis, the Communist regime was forced to temporarily “unleash” the intellectual community to reduce social pressure. Vietnamese writers took advantage of the period to continue the work of the Nhân Văn Giai Phẩm group, which had been crushed some 30 years earlier.

They began a movement that even their colleagues overseas enthusiastically embraced. It became known by the title of a 797-page anthology: Trăm hoa vẫn nở trên quê hương (Hundreds of Flowers Still Flourishing in the Motherland). Drawn from the depths of their hearts and filled with vibrant realism, the collection is now preserved at the U.S. Library of Congress.

Efforts in Reviving Southern Literature

In the late 2000s, before the explosion of the Internet, the Hà Nội-based critic Vương Trí Nhàn expressed concerns that Southern literature might disappear entirely. Having secretly read and fallen in love with these works before 1975, he understood what was at stake.

In a conversation with the critic Thụy Khuê, Nhàn said if these materials were not collected quickly, they would soon be lost and forgotten. His concern highlighted the NVC’s ongoing prohibition against Southern literature, more than three decades since the regime’s initial campaign of book burning and imprisonment.

In truth, the exile community had already begun efforts to revive Southern literature and arts. Cassette tapes of Southern music were reproduced and sold in Vietnamese refugee settlements in America and around the world. Books that were banned, confiscated, and burned by the Communist regime have also been photographed; many were borrowed from the Library of Congress and Cornell University, and reprinted overseas.

Pre-war literary works reprinted in the South pre-1975 have also been photocopied and were republished. Furthermore, there were memoirs written by writers from all walks of life, including former communist party members who have come to their senses.

The advent of the Internet and its widespread use over the past 30 years contributed to the revival and preservation of Vietnamese literature and art in the Vietnamese diaspora.

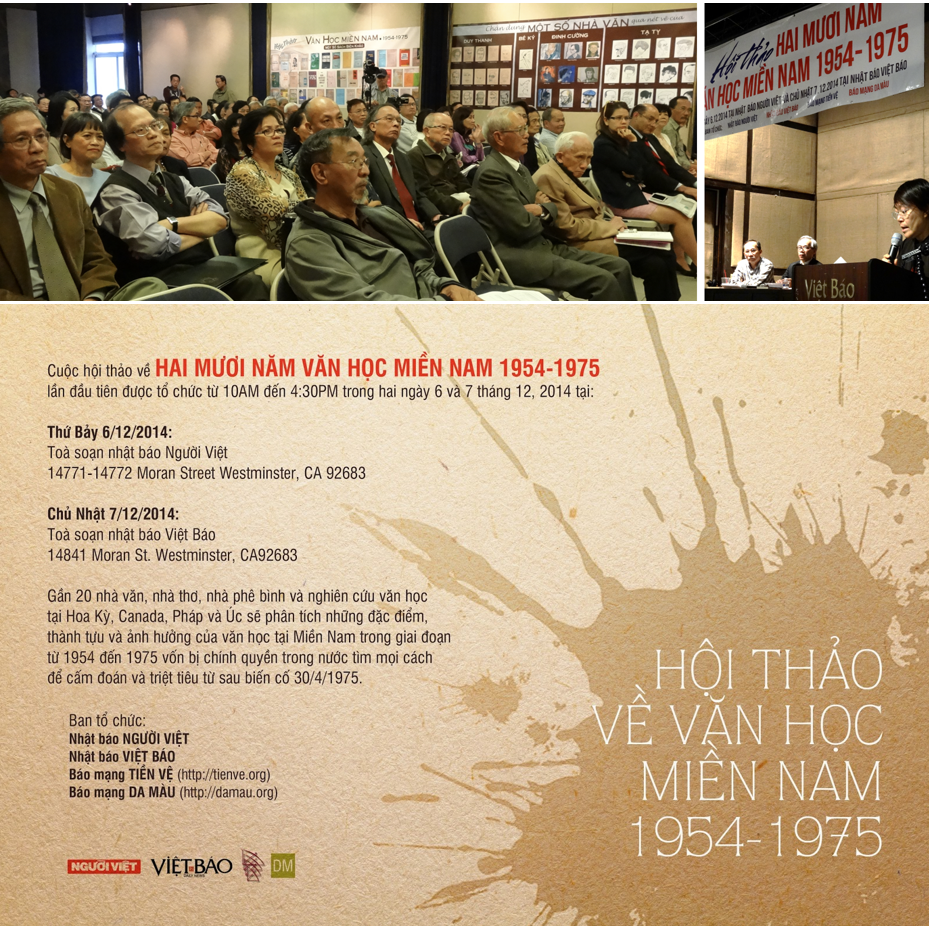

Several conferences have also taken place to discuss and document the various aspects of South Vietnamese cultural life during the second decade of the 21st century. On the 48th anniversary of the fall of Saigon, these preservation efforts were detailed in an article titled, “Công trình vãn hồi sách báo Miền Nam & nghiên cứu kinh nghiệm kiến quốc 1955-1975 của VNCH” (Projects in restoring books and newspapers of South Vietnam & studies of RVN’s nation building in war).

This piece briefly introduces the websites that currently preserve significant numbers of books, whether retyped or scanned, and digitized copies of newspapers published during the Republic era.

Over the past decade, new academic research has shed light on the wartime nation-building efforts of the Republic of Vietnam. This effort is spearheaded by a number of young professors of Vietnamese origin and their American colleagues at universities across the United States and Canada.

Thanks to the Internet, their findings on the RVN’s politics, economics, society, education, literature, and art have reached a wider audience—from the Vietnamese diaspora to the people within Vietnam itself. This is an indispensable part of Vietnam’s history, which the Hanoi regime still denies.

On the 50th anniversary of the day our country and people saw their lives turned upside down, this piece serves as both a reflection and commemoration. I sincerely hope that it may offer inspiration for future generations to learn more about this splendidly artistic and humanistic era of the South. In doing so, perhaps they can find an answer to this question: Did this vibrant culture flourish despite the war, or was it, in some profound way, thanks to it?

Southern Literature: From Death to Resurrection in Its Homeland

A review of recent positive developments in Vietnam offers a slight glimmer of hope. In the past 10 years, the literature that the Communist regime once tried to eradicate has seen a strong resurgence, as if the seeds planted in the minds of the previous generation that went to “liberate” the South have finally sprouted and begun to grow.

A number of books by Southern authors have been reprinted and distributed, while a number of academic studies have also been conducted. This is a good thing for both Vietnamese arts and letters.

Academic research has also reflected this trend. For instance, a 2021 conference sponsored by the University of Hamburg, “Literature and Journalism in the Republic of Vietnam (1955-1975) and the Reception of Western Thought,” featured dozens of research papers from scholars within Vietnam.

An even more in-depth example is Trần Hoài Anh’s doctoral thesis, Lý luận phê bình văn học đô thị miền Nam 1954-1975 (Southern Urban Literature Criticism 1954-1975), submitted over 10 years ago. The author later re-edited and published his thesis as a book titled, Lý Luận-Phê Bình Văn Học Miền Nam 1954-1975–Tiếp Nhận Và Ứng Dụng (Southern Literature Criticism Theory 1954-1975–Reception and Application). For its publication, he notably dropped the term “văn học đô thị” (“urban literature” ) from the original title. Earlier this year (2025), the book won the Criticism Award from the Vietnam Writers Association.

In an interview, Trần Hoài Anh said:

“More than 10 years ago, choosing the topic ‘Theory of criticism of Southern urban literature 1954-1975’ for my PhD thesis was quite a risk for me. But perhaps thanks to the change in the thinking system of literary research during the renovation period when a series of taboo literary phenomena such as the New Poetry Movement [Phong trào Thơ mới], Tự Lực Văn Đoàn [Self-reliance Literary Group], Nhân Văn Giai Phẩm… were recognized, re-evaluated and ‘exonerated’ in literary life, choosing the topic of my thesis did not encounter any obstacles.

This is a good sign for the nation’s literary life. Southern literature before 1975, which was considered ‘decadent’ and ‘reactionary literature’ as some people labeled it not too long ago, is now officially ‘properly’ studied in the academic environment at a prestigious scientific research institute, the Vietnam Institute of Literature.

At the same time, the reappearance of Southern literature before 1975 in the country’s literary life was an inevitable development in changing the theoretical thinking system of literary criticism during the renovation period, and is one of the achievements of the country’s renovation, including the renovation of literature.”

A half a century later, true political reconciliation among the Vietnamese people within and without the country has not yet been achieved. But where politics has failed, a path towards unity may be found through a literary body filled with humanity—the literature of the South.

- Trăm hoa đua nở trên đất Bắc. Saigon : Mặt-trận bảo-vệ tự-do văn-hóa, 1959. https://lccn.loc.gov/75986982. Also at https://www.scribd.com/document/535108983/Tr%C4%83m-Hoa-%C4%90ua-N%E1%BB%9F-Tren-%C4%90%E1%BA%A5t-B%E1%BA%AFc-NXB-Sai-Gon-1959-Hoang-V%C4%83n-Chi-330-Trang

- Thụy Khuê, “Văn học miền Nam,” http://thuykhue.free.fr/stt/v/VanHocMienNam.html

- “Vì sao triết lý giáo dục của Việt Nam Cộng Hòa mãi trường tồn?” https://www.rfa.org/vietnamese/in_depth/why-the-educational-philosophy-of-south-vn-still-exits-forever-11282018124142.html

- “Book burning of the South Vietnam – Miền Bắc đốt sách của Miền Nam như thế nào?” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_mjoRthhK_s

- Võ Phiến, Văn học Miền Nam Tổng quan, https://www.tienve.org/home/literature/viewLiterature.do;jsessionid=DA3D1FCFB36FBA80D3326C66330DD83E?action=viewArtwork&artworkId=3056

- Trùng Dương, “Phụ nữ viết văn thời Cộng hòa,” https://www.toiyeutiengnuoctoi.com/phu-nu-viet-an-thoi-viet-nam-cong-hoa/

- “Hốt xác đồng bào tử nạn trên ‘Đại lộ Kinh hoàng’,” https://usvietnam.uoregon.edu/tu-lieu-lich-su-hot-xac-dong-bao-tu-nan-tren-dai-lo-kinh-hoang-1972/

- Vân Nguyễn-Marshall (2018): “Appeasing the Spirits Along the ‘Highway of Horror’: Civic Life in Wartime Republic of Vietnam, War & Society,” DOI: 10.1080/07292473.2018.1469107, https://doi.org/10.1080/07292473.2018.1469107

- Trùng Dương hội luận về văn học miền Nam với các bạn trẻ:https://youtu.be/sIXFLydUMLM?si=8nmIRTYZ3uKa58cu

- Hồi ký Nguyễn Hiến Lê, Tập I, II & III, Văn Nghệ xuất bản 1988, https://hoangkyblog.wordpress.com/2023/05/11/toan-bo-hoi-ki-nguyen-hien-le-nha-xuat-ban-van-nghe-california-hoa-ky-1989/. The Library of Congress has a copy of Volume III, https://lccn.loc.gov/90112116

- Nhật Tiến, “Hoàn Cảnh Sáng tác Của Anh Chị Em Văn Nghệ Sĩ Ở Quê Nhà Sau 30-4-1975,” https://nhavannhattien.wordpress.com/hoan-canh-sang-tac-cua-anh-chi-em-van-nghe-si-o-que-nha/

- Nguyễn Vy Khanh, “Văn Học Miền Nam Tự-Do 1954-1975 (Phần 2): Một thời tưởng tiếc,” https://damau.org/35752/van-hoc-mien-nam-tu-do-1954-1975-phan-ii

- Nguyễn Vy Khanh, Văn Học Miền Nam 1954-1975, Quyển Thượng và Quyển Hạ, https://www.amazon.com/V%C4%83n-H%E1%BB%8Dc-Mi%E1%BB%81n-Nam-1954-1975/dp/1989924956

- Nhã Ca, “Người cầm bút thời Việt Nam Cộng Hòa,” Chương 13, tr. 280-290, Việt Nam Cộng Hòa 1955-1975 – Kinh Nghiệm Kiến Quốc, chủ biên Vũ Tường và Sean Fear, Văn Học 2022, https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/viet-nam-cong-hoa-kinh-nghiem-kien-quoc-tuong-vu/1140834973?ean=9798765508558

- Trùng Dương, “UC Berkeley Nhìn Lại 20 Năm VNCH Xây Dựng Quốc Gia Trong Thời Chiến,” Part 1, https://damau.org/44777/uc-berkeley-nhin-lai-20-nam-vnch-xay-dung-quoc-gia-trong-thoi-chien-ky-12, and Part 2, https://damau.org/44805/uc-berkeley-nhin-lai-20-nam-vnch-xay-dung-quoc-gia-trong-thoi-chien-ky-22

- Trăm hoa vẫn nở trên quê hương: Cao trào văn nghệ phản kháng tại Việt-Nam, 1986-1989, tuyển tập. Reseda, CA : Le Tran Pub. Co., c1990. 797 p. : ill. ; 24 cm. PL4378.4 .T7 1990, https://lccn.loc.gov/91164038

- Thụy Khuê, “Nói chuyện với nhà phê bình Vương Trí Nhàn,” http://thuykhue.free.fr/stt/v/VuongTriNhan-NC-VHMN.htm

- Trùng Dương, “48 năm sau nhìn lại: Công trình vãn hồi sách báo Miền Nam & nghiên cứu kinh nghiệm kiến quốc 1955-1975 của VNCH,” https://diendantheky.net/trung-duong-48-nam-sau-nhin-lai-cong-trinh-van-hoi-sach-bao-mien-nam-nghien-cuu-kinh-nghiem-kien-quoc-1955-1975-cua-vnch/

- “Chuyện trò với Giáo sư Vũ Tường về cuộc hội thảo Kinh nghiệm kiến quốc trong thời chiến của Việt Nam Cộng hoà, 1955-1975 tại UC Berkeley,” https://vietbao.com/a258967/chuyen-tro-voi-giao-su-vu-tuong-ve-cuoc-hoi-thao-kinh-nghiem-kien-quoc-trong-thoi-chien-cua-viet-nam-cong-hoa-1955-1975-tai-uc-b

- Việt Nam Cộng Hòa 1955-1975: Kinh Nghiệm Kiến Quốc, Vũ Tường & Sean Fear chủ biên, https://damau.org/71006/viet-nam-cong-ha-1955-1975-kinh-nghiem-kien-quoc-vu-tuong-sean-fear-chu-bin

- Webinar – Literature and Journalism in the Republic of Vietnam (1955 – 1975) and the Reception of Western Thought, https://www.aai.uni-hamburg.de/soa/aktuelles/21-06-11-viet-literature-conference.html; a list of paper presentations, https://www.aai.uni-hamburg.de/soa/aktuelles/21-06-11-viet-literature-conference/programme-literature-and-journalism.pdf; and “A report from the conference on Literature and Journalism in the Republic of Vietnam (1955 – 1975) and the Reception of Western Thought from the 11th of July, 2021,” https://www.aai.uni-hamburg.de/soa/aktuelles/21-07-12-conferencereport-vietnam.html

- “Nhà phê bình Trần Hoài Anh: Văn học miền Nam là một di sản,” https://vanhocsaigon.com/nha-phe-binh-tran-hoai-anh-van-hoc-mien-nam-la-mot-di-san/

- “Văn học: Lý Luận-Phê Bình Văn Học Miền Nam 1954-1975 – Tiếp Nhận Và Ứng Dụng PDF,” https://yds.edu.vn/ly-luan-phe-binh-van-hoc-mien-nam-1954-1975-tiep-nhan-va-ung-dung-pdf/

- “Nhà nghiên cứu Trần Hoài Anh: Văn học nghệ thuật miền Nam trước 1975 – Bước hòa hợp mới,” https://vanhocsaigon.com/nha-nghien-cuu-tran-hoai-anh-van-hoc-nghe-thuat-mien-nam-truoc-1975-buoc-hoa-hop-moi/