In what has become a predictable annual assessment, the U.S. State Department released its 2024 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, concluding that Việt Nam had “no significant changes in the human rights situation” over the past year. The report methodically details a landscape of significant and ongoing human rights violations within the one-party Communist state.

While Việt Nam’s constitution pays lip service to various freedoms, the report highlights how the government continues to use vague national security laws to ensure that those rights remain purely theoretical. The key issues listed are a familiar litany of abuses: arbitrary or unlawful killings; torture and cruel treatment by government agents; transnational repression against critics abroad; and severe restrictions on freedoms of expression, media, religion, and association.

The arbitrary arrest and detention of political activists remains a severe problem. Vietnamese law conveniently allows the government to arrest and detain individuals in national security cases “until the investigation finishes,” a loophole that effectively sanctions indefinite detention.

The report provides the example of Y Thinh Niê, an ethnic minority religious leader in Đắk Lắk Province, whose home was searched without a warrant and who was subsequently detained for two months without charges as of November 2024. The practice of holding individuals in pretrial detention for periods exceeding the legal maximum was also noted, with the case of Nguyễn Duy Hướng, held since his 2021 arrest, cited as an example of this impunity.

Hà Nội’s Long Arm of Coercion

In a move that blatantly disregards both Thai sovereignty and international refugee conventions, the report highlights Hà Nội’s practice of transnational repression. The most stark example is the case of Dương Văn Thái, a political blogger and a UNHCR-recognized refugee living in Bangkok. In April 2023, he was forcibly returned to Việt Nam by what human rights groups report were Vietnamese authorities.

Upon his return, state media spun the narrative that Thái was detained for illegally entering the country. However, he was ultimately tried and, on Oct. 30, 2024, sentenced to 12 years in prison and three years of probation for “disseminating antistate propaganda” related to his YouTube channel. This incident is part of a broader pattern where Ministry of Public Security officers reportedly visit ethnic minority refugee communities in Thailand to “interrogate and pressure them to return to Việt Nam,” and threaten them with arrest if they refuse.

Deaths in Custody and a Culture of Impunity

The State Department report includes several accounts of arbitrary or unlawful killings by government agents, particularly of detainees in police custody. One prominent case was that of Vũ Minh Đức, who was summoned for questioning in Đồng Nai Province on March 22, 2024 for “disturbing public order.” He fainted during the interrogation and died later that day in a hospital. The details from the hospital-issued death certificate list “cardiac arrest, acute kidney damage, acute liver failure, and soft tissue damage to the legs.” His family added that his body showed clear signs of a beating, including dried blood and bruising on his chest and thighs.

While the arrest of a police investigator in November on charges of “using corporal punishment” offers a rare glimmer of accountability in Đức’s case, the wider pattern is one of impunity. The report notes that despite Supreme People’s Court guidance to charge officers responsible for deaths in custody with murder, they typically face lesser charges, and accountability often comes several years after the death, if at all.

Silencing Critics

The government’s crackdown on freedom of expression was exemplified by the case of Dương Tuấn Ngọc, a teacher from Lâm Đồng Province. On April 24, 2024, a court sentenced Ngọc to seven years in prison and three years of probation for spreadingantistate propaganda; authorities accused him of posting articles and videos on social media that “mocked, defamed, and criticized the government and the CPV’s policies.”

His case is an example of how Việt Nam’s legal arsenal is used to silence dissent. The government controls all major media, and pervasive self-censorship is the norm. Foreign journalists require formal permission to travel outside Hà Nội, and live foreign television programming runs on a 10-60 minute delay, presumably to ensure no unapproved information accidentally reaches the public.

Restricting Workers’ Rights

The report details the methodical restrictions on workers’ freedom of association, creating a system perfectly rigged to look like it protects workers while ensuring they have no real power. The law does not permit independent unions; all labor organizations must operate under the Việt Nam General Confederation of Labor (VGCL), a CPV-run entity that answers to the Việt Nam Fatherland Front.

In a particularly telling example of legislative hypocrisy, the labor code technically allows for the formation of independent worker organizations, but the government has conveniently “not issue[d] an implementing decree necessary for their establishment or operation.” Likewise, the process for a legal strike is made so intentionally cumbersome that it comes as no surprise that, as in previous years, there were zero legal strikes.

Weaponizing Mental Health Against Activists

In a tactic reminiscent of methods used by other authoritarian regimes, the report highlights the use of forced mental health evaluations as a tool of political repression. The case of activist Nguyễn Thúy Hạnh is a key example. Authorities held her in pretrial detention from 2021 until her trial in July. During this period, from April 2023 to March, she was subjected to compulsory treatment for depression at the National Institute of Forensic Psychiatry. She was later granted an early medical release due to a serious medical condition, but the weaponization of medicine to break the will of a dissident had already been clearly demonstrated.

Beyond political repression, the report sheds light on severe societal issues that the government fails to effectively address. Child labor remains prevalent, with authorities estimating that more than one million children between the ages of 15 and 17 work. Approximately 20 percent of them work more than 40 hours per week, and nearly 50 percent work in a hazardous environment. This exploitation comes at the cost of their future, as nearly 49 percent of these child workers do not attend school. The government’s enforcement of child labor laws is ineffective, with penalties rarely applied against violators.

A Portrait of Stagnation and a Glimmer of Hope

The U.S. State Department’s 2024 report on human rights in Việt Nam is, above all, a portrait of deliberate stagnation. The verdict of “no significant changes” is a damning indictment of a government that has perfected the machinery of control and sees no incentive for reform. The grim tableau detailed in the report—of activists abducted from foreign soil, detainees dying under suspicious circumstances after interrogation, teachers jailed for criticizing the government, and a mechanism that offers the illusion of worker rights while denying any real power—is the intended outcome of a system designed to crush dissent and preserve the absolute authority of the Communist Party of Việt Nam.

What the report highlights most is the systemic hypocrisy at the heart of the Vietnamese state. It is a government that signs international conventions and enshrines human rights in its constitution, only to wield a legal code filled with vague national security articles to strangle those very rights. Việt Nam’s poor human rights record has become a reflection of a semantic game that uses the language of rights as a shield to deflect international criticism while ensuring that the reality on the ground remains one of absolute control.

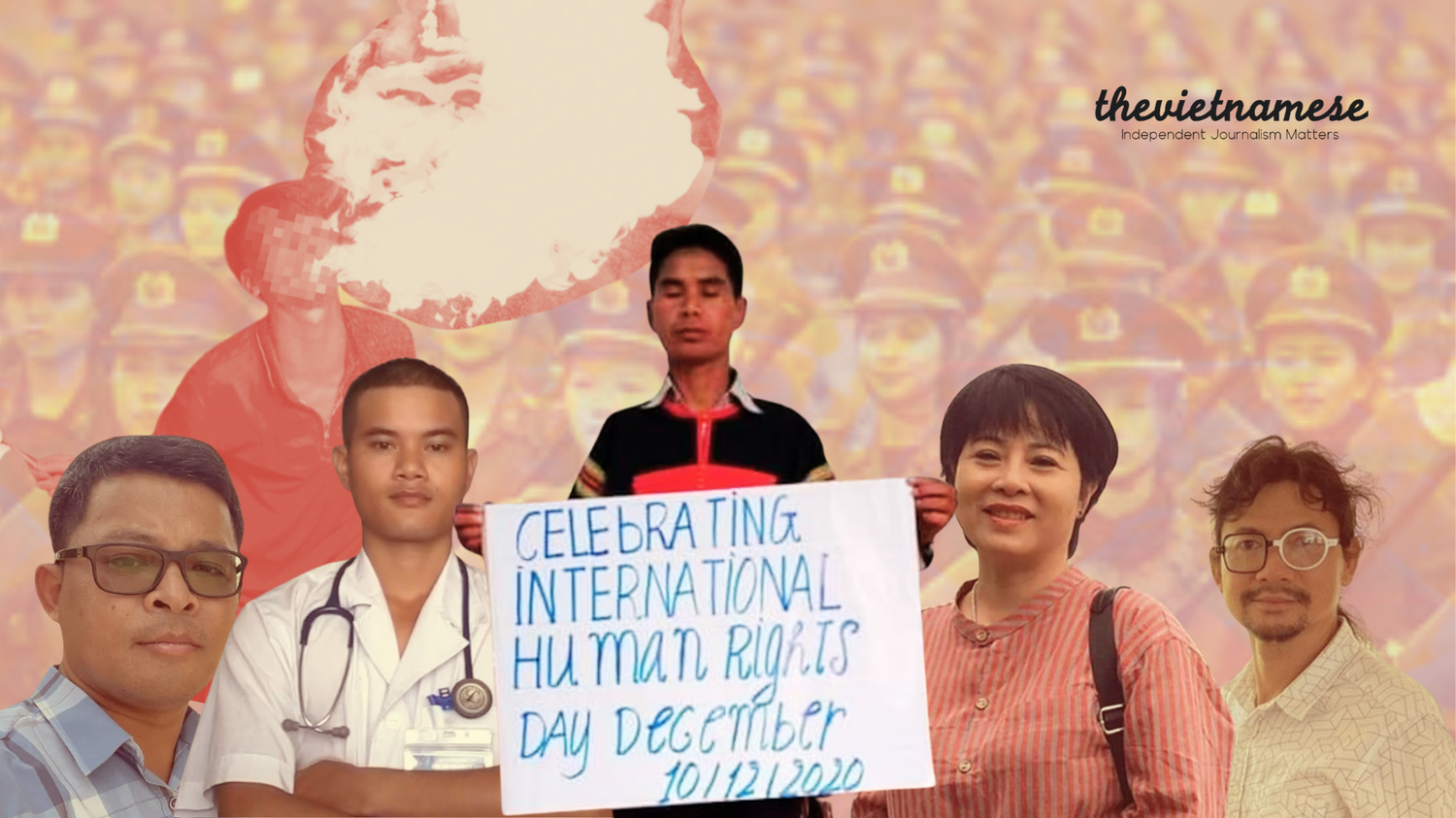

However, if the report details the depths of state repression, it also inadvertently highlights the resilience of the Vietnamese human spirit. For every abuse documented, there is a victim who dared to speak out: a blogger like Dương Văn Thái, a teacher like Dương Tuấn Ngọc, or an activist like Nguyễn Thúy Hạnh. While the Vietnamese state has shown little capacity for self-reform, the persistence of its people in demanding basic human dignity continues unabated. It is in their unyielding demands, documented year after year, that any real hope for the future of human rights in Việt Nam resides.

- U.S. Department of State. (2025, August 12). 2024 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Vietnam. https://www.state.gov/reports/2024-country-reports-on-human-rights-practices/vietnam

- RFA Vietnamese (2023, November 3). Unofficial Vietnamese church members languish in detention. Radio Free Asia. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/vietnam/church-11022023163446.html

- The Vietnamese Magazine. (2024, October 31). Vietnam sentences blogger Duong van Thai to 12 years after alleged kidnapping in Thailand. https://www.thevietnamese.org/2024/10/vietnam-sentences-exiled-blogger-duong-van-thai-to-12-years-after-alleged-kidnapping-in-thailand

- RFA Vietnamese. (2024, March 26). Vietnamese man dies in custody, body indicates torture, family says. Radio Free Asia. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/vietnam/vietnam-suspicious-death-03262024002734.html

- RFA Vietnamese. (2024, April 24). 2 teachers jailed for criticizing authorities on social media. Radio Free Asia. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/vietnam/teachers-jailed-04242024183923.html

- The Vietnamese Magazine. (2024, October 10). Activist Nguyen Thuy Hanh, founder of the Charity 50K Fund, released upon completion of her sentence. https://www.thevietnamese.org/2024/10/activist-nguyen-thuy-hanh-founder-of-the-charity-50k-fund-released-upon-completion-of-her-sentence