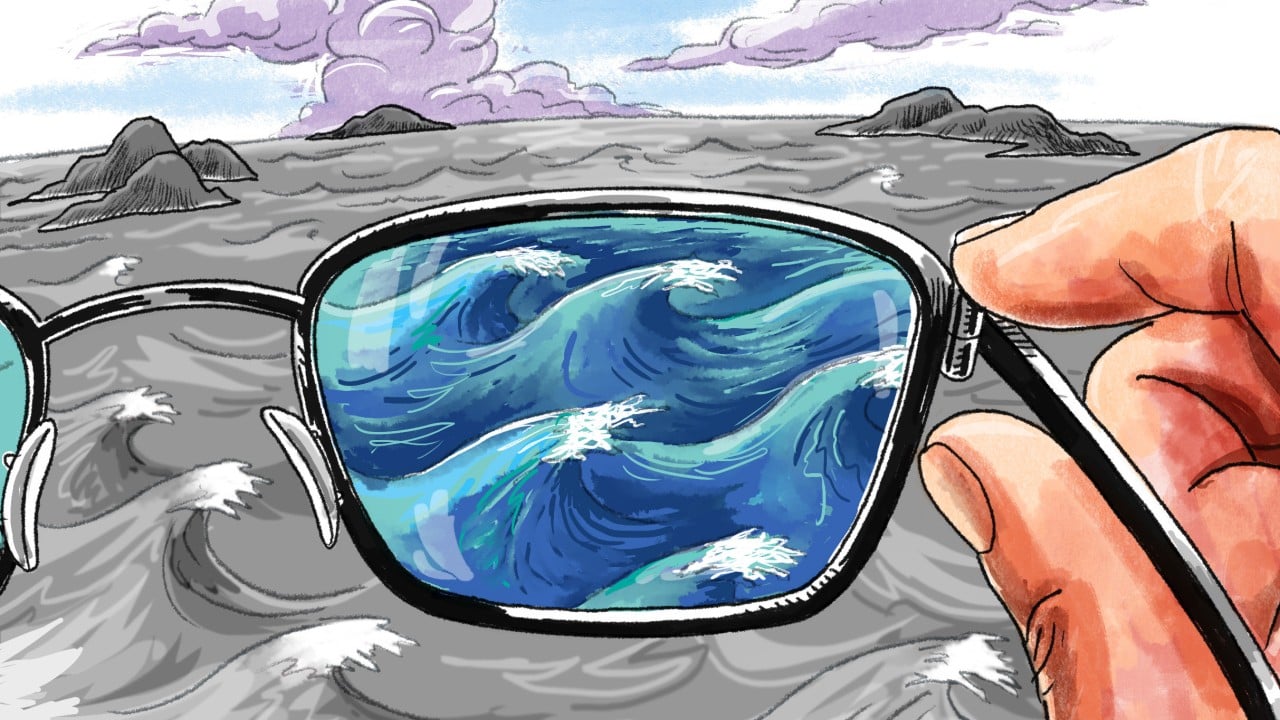

Few disputes in Asia are as enduring – and as polarising – as those over the South China Sea. For more than a decade, two sharply opposed narratives have dominated. In one, Beijing is seen as using force, or the threat of force, to change the status quo, undermining peace and stability. In the other, China is portrayed as exercising restraint, acting within its rights and working to safeguard regional stability.

Advertisement

These perspectives are not merely different; they are mutually exclusive. One side’s defensive action is interpreted as aggressive by the other, reinforcing mistrust and escalation. Measures to enhance one party’s security inevitably diminish the sense of security for others. This makes de-escalation difficult and drives the dispute beyond legal or territorial boundaries into the realm of identity, national pride and historical grievance. Without narrowing this gulf, a peaceful resolution remains remote.

At its core, the divergence stems from conflicting national interests. Yet the roots run deeper, in the incomplete territorial arrangements left after the second world war.

The rapid onset of the Cold War froze parts of the post-war settlement in ambiguity. Treaties such as the 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty and 1952 Sino-Japanese Peace Treaty required Japan to renounce the Spratly and Paracel Islands but did not specify their new sovereign owner. Beijing maintains these territories are historically Chinese, before Japan’s wartime seizure.

Other claimants read the record differently. Some argue Japan’s renunciation did not automatically transfer sovereignty to China, rendering the islands terra nullius – open to lawful occupation.

Advertisement

A further source of contention is the mismatch between the historical and legal frames of reference. China grounds its claim heavily in history, citing the Cairo Declaration, Potsdam Proclamation, Japanese Instrument of Surrender and its own 1946 reclamation of the Dongsha, Zhongsha, Xisha and Nansha Islands. It points to maps published in 1947 and the erection of stone markers – acts uncontested at the time – as evidence of sovereignty.