Vietnamese citizens have just lived through months of earth-shaking political upheaval—yet not a single meaningful public conversation has unfolded online. The dissolution and merging of government bodies, a constitutional amendment to eliminate the district level, the redrawing of provincial boundaries—all met with silence.

Among Việt Nam’s political observers, there seems to be a consensus: the year 2016 marked a turning point in the Communist Party’s strategy for social control. And at the heart of this strategy is the Internet—now one of the regime’s primary targets.

Anyone who lived in or closely observed Vietnamese society before 2016 would likely recall a very different country. It was a time of economic boom and relatively greater political openness. The Internet was largely beyond the reach of state control, and foreign platforms like Yahoo, Google, and Facebook rushed into Việt Nam, quickly dominating the digital landscape.

For the first time, ordinary citizens had access to powerful, free tools to express themselves. Despite countless challenges, civil society began to blossom, both online and offline. Protest movements gradually normalized the very idea of public demonstration, to the point where a draft protest law was even being considered by the National Assembly.

But everything began to spiral downward following the 12th National Congress of the Communist Party in January 2016. After one term in office, General Secretary Nguyễn Phú Trọng was re-elected in a process that saw him consolidate power dramatically, most notably by removing his chief political rival, then–Prime Minister Nguyễn Tấn Dũng.

From that point on, the party leader consistently invoked the need to defend the Party’s leadership against all enemies, both internal and external. A conservative tide took hold, and a new consensus emerged among the leadership: they must seize control of the Internet, at any cost.

And they have succeeded.

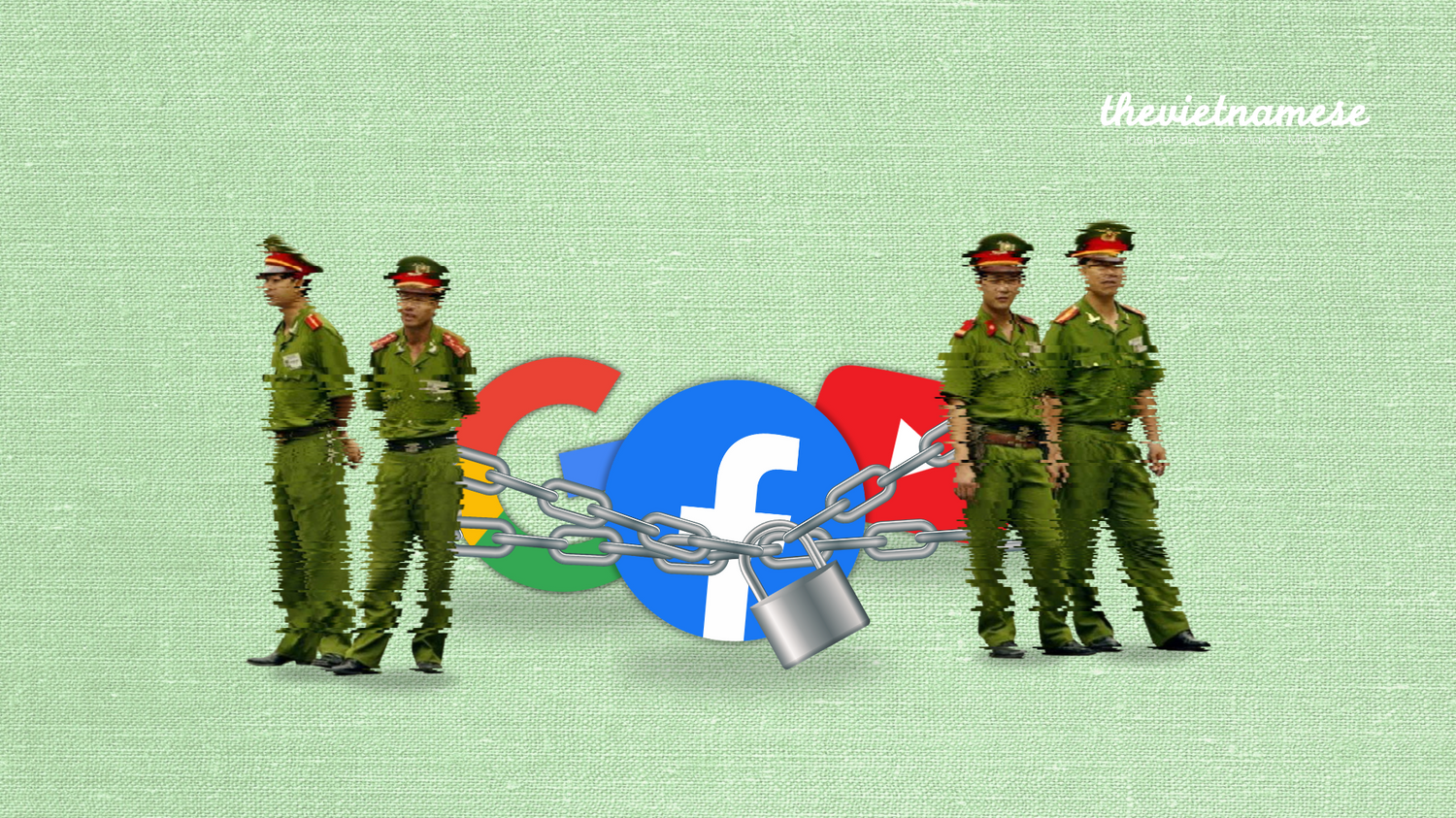

The story of how the Vietnamese government brought foreign tech giants to heel, a process detailed in the 2024 report “How Foreign Tech Companies Have Failed to Uphold Human Rights in Vietnam,” is best exemplified by the case of Facebook. The social media giant expanded into Việt Nam in 2009, perfectly timed to fill the void left by the declining Yahoo! 360 blog platform. It quickly became the central hub for a new wave of civic activism.

Within just two years, Facebook was at the heart of one of the most unprecedented protest movements in post-1975 Việt Nam—an 11-week series of anti-China demonstrations in the summer of 2011, often labeled “Revolution 2.0” or the “F Generation.” In the years that followed, the country’s most vibrant social movements unfolded on the platform, from the 2013 constitutional reform campaign, to the 2014 anti-China protests, and the 2015 Hà Nội tree-cutting protests.

Facebook had become an essential media ally for civil society, powering every wave of civic action and remaining a reliable platform for activists up until the massive protests against the Formosa steel plant in 2016 and the proposed special economic zones in 2018.

So, what changed?

The shift began after 2017, when the number of Facebook posts by Vietnamese users removed at the government’s request started to steadily increase. While the exact percentage of takedown requests Facebook complies with remains unclear, the Vietnamese government has claimed compliance rates as high as 90–95%. Google has faced similar pressures, especially on its YouTube platform. The company’s own transparency reports reveal that up to 90% of the content it has removed at Hà Nội’s request involved criticism of the government.

The Vietnamese authorities achieved this compliance through a three-pronged strategy of economic and legal coercion.

First, they leveraged Việt Nam’s lucrative market to pressure foreign tech firms into submission. With annual revenues in the billions, companies like Facebook and Google had little incentive to walk away. To increase this pressure, the Ministry of Information and Communications even pushed domestic advertisers to stop placing ads on non-compliant foreign platforms—a tactic that resembled economic blackmail.

Second, the government introduced a series of new regulations aimed squarely at foreign tech companies. The 2018 Cybersecurity Law is a prime example, requiring foreign firms to store user data within Việt Nam and to open local offices or branches.

The government’s goal was not to rein in domestic companies, which it could already control, but to create a legal hammer to bring global giants to heel. Sky-high regulatory demands, like those in the 2018 Cybersecurity Law or Decree 147/2024, weren’t necessarily meant to be fully implemented—they were bargaining chips. This became clear when Decree 53/2022 later dropped the requirements for local data storage and offices once the government had achieved its real goal: compliance with its censorship requests.

When companies did resist, the authorities didn’t hesitate to use brute force. In early 2020, following the deadly Đồng Tâm land rights incident, the government throttled Facebook’s bandwidth for months, rendering it nearly unusable until the company agreed to tighten its censorship of political content.

The final prong of the strategy was to go on the offensive. Deleting posts was no longer enough; the goal was to dominate the digital battlefield. The government deployed an army of online propagandists, expanding its use of “public opinion shapers” and the notorious Force 47. It also established Steering Committee 35, a nationwide network mobilizing everyone from party cadres to students to actively “fight back” against information labeled as harmful or toxic.

This multifaceted strategy, combined with the arrests and imprisonment of domestic users, proved resoundingly successful. The foreign tech giants capitulated. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, Việt Nam’s online space has become noticeably more docile, with no significant social movements emerging from it. Platforms like Facebook and Google are now often accused of colluding with the government to suppress free expression.

And General Secretary Tô Lâm, the chief architect of this control strategy during his time as Minister of Public Security, now stands at the pinnacle of power, with little reason to believe he will loosen this hard-won grip on the Internet anytime soon.