Liquid water may be locked in rock just a few kilometres beneath Martian ground – much closer to the surface of the red planet than previously thought.

Advertisement

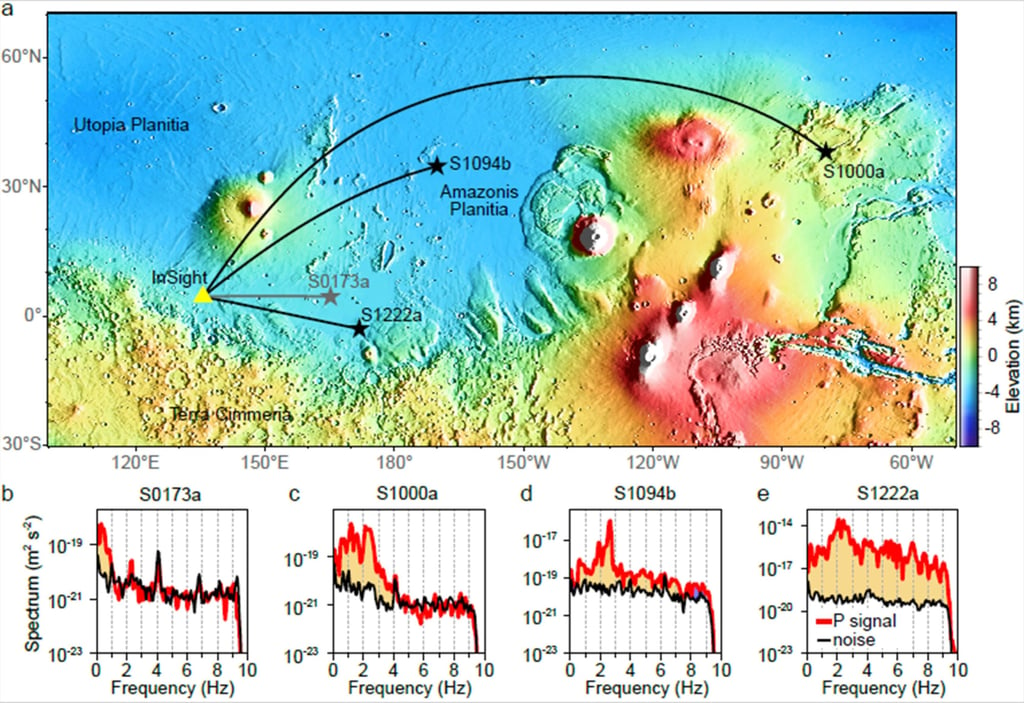

Using data from Nasa’s now-retired InSight lander, a China-led international team of researchers analysed seismic waves from “marsquakes” and meteorite impacts recorded between 2018 and 2022. They revealed a mysterious zone in the planet’s crust they said was best explained by a layer of water-saturated rock.

If confirmed, this underground layer – between 5.4km and 8km (3.3-5 miles) deep – could hold as much water as a global layer up to 780 metres (2,550 feet) thick, according to their paper published in National Science Review last month.

The amount matched what scientists believe to be Mars’ missing water, after taking into account the water that has escaped into space, become locked into rocks or remains as ice and vapour, said the researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the Australian National University and the University of Milano-Bicocca.

“Our results provide the first seismic evidence of liquid water at the base of the Martian upper crust, shaping our understanding of Mars’ water cycle and the potential evolution of habitable environments on the planet,” they wrote in the paper.

Advertisement

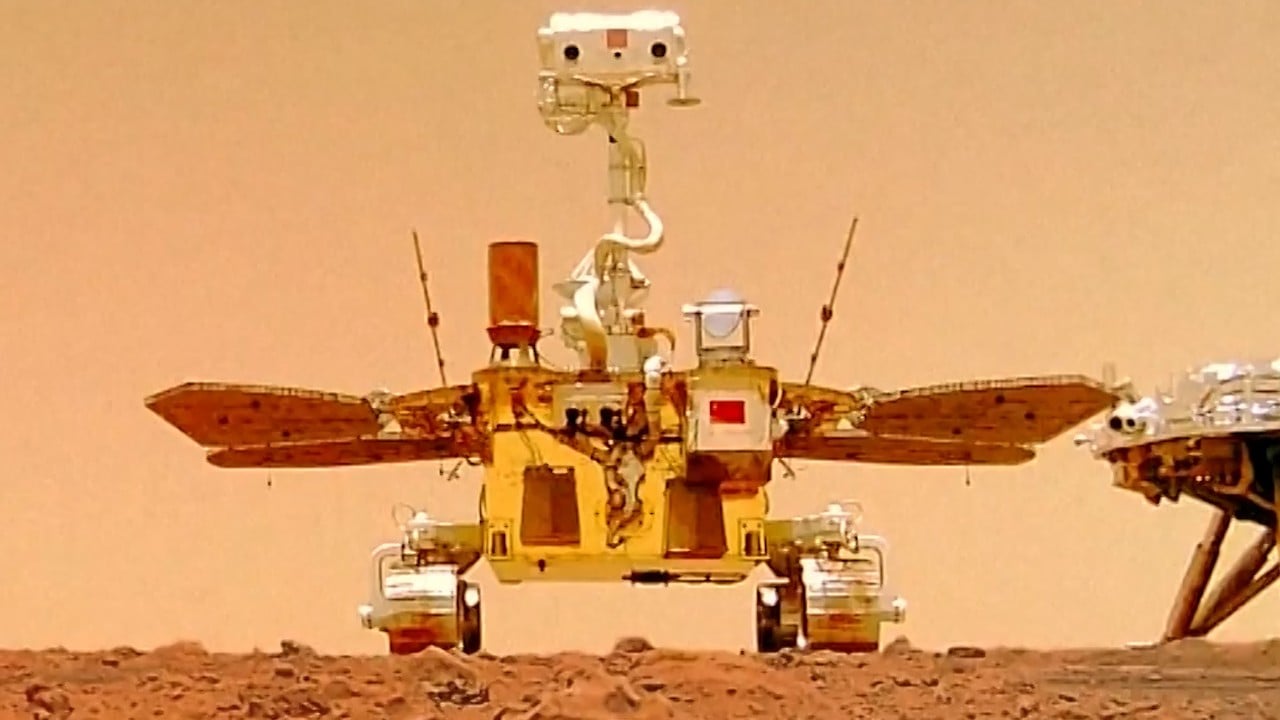

Nasa’s InSight lander arrived on Mars in 2018 with a unique mission: not to roam the surface, but to listen to what was happening beneath it. For four years, it used a sensitive seismometer to detect subtle ground movements caused by crustal stress and meteorite impacts.