Losing our baby teeth is a rite of passage for everyone, often requiring clever strategies to remove those stubborn little gnashers.

For nearly 5,000 years, the indigenous communities of Taiwan practised a tradition called teeth ablation, the deliberate removal of healthy adult teeth, primarily targeting the visible front-facing anterior teeth. This practice would become a significant tradition that persisted for millennia.

According to a recent study published in Archaeological Research in Asia that analysed research reports from over 250 archaeological sites of Austronesian peoples in Taiwan, tooth ablation was a widespread custom that migrated along with the communities.

“Our paper suggests that this practice spread with ancient Austronesian speakers as they migrated from Taiwan to [islands in] Southeast Asia. This is supported by allied evidence of the custom and their material culture and agricultural practices,” said Zhang Yue, a study author from the Department of Archaeology and Natural History at the Australian National University in Canberra.

Austronesians were a large ancient ethnic group in Taiwan that migrated southward into Southeast Asia, Micronesia and Polynesia. The paper suggested that tooth ablation should be considered a “diagnostic cultural trait” of the ancient Austronesians.

Zhang told the Post that the tooth ablation culture likely migrated from mainland China along with other Neolithic customs like ceramics making, weaving techniques, and agriculture.

The researchers dated the earliest examples of tooth ablation in Taiwan to between 4,500 and 4,800 years ago, with the earliest examples in the region appearing in north China around 6,000 years ago.

The most recent examples of tooth ablation appeared as late as the middle of the 20th century, with Zhang saying the influence of Western culture has driven the practice out of existence.

“In the case of Taiwan, ethnic groups in the mid-20th century were practising patterns very similar to those from the Neolithic Age,” said Zhang.

This tradition of removing healthy teeth had diverse cultural significance across different peoples.

One of the most frequently cited reasons for tooth ablation among adults was to distinguish humans from animals.

Zhang said the Austronesians believed removing the teeth “would reduce the protrusion of the mouth, a characteristic they associated with animals”.

Legends also played a role, as the Bunun people removed their teeth to honour their ancestors’ deeds during battles from past generations. That group, along with the Atayal people, also removed teeth due to sexual lessons that were passed down via a famous folktale.

Beyond beautification or lore, tooth ablation may have also served medical purposes, such as enhancing the administration of medicine. Alternatively, it could have been a precautionary measure to ensure individuals could still eat if they developed lockjaw.

Finally, the researchers proposed that tooth ablation may have signified who was part of the community. The Tsou group identified people with all of their teeth as criminals who had fled.

The researchers think tooth ablation was likely performed by striking or pulling the tooth. Both processes would have been excruciating, which may have been a critical feature that turned tooth ablation into a rite of passage.

“Experiencing and overcoming the ‘pain’ might be one of the important aspects of this ritual,” said Hung Hsiao-chun, a study author also from the Department of Archaeology and Natural History at the Australian National University.

“For modern individuals, maintaining a complete set of teeth is important, which makes it challenging to understand this custom from a contemporary perspective,” she said.

“This research has provided us with insights into the spiritual world of ancient populations and can help readers investigate and respect diverse cultural customs among modern ethnic groups.”

The team did not believe tooth ablation was used to signify social classes, as it was widely popular among broad swaths of the population, including among both sexes.

Mike Carson, another study author from the Micronesian Area Research Center at the University of Guam, said: “In my understanding, the tooth ablation is a rite of passage for people generally, without a restriction of status.”

He added that he hopes the research helps readers “develop new ideas about the [cultural depth] of tooth ablation and how the practice potentially can relate to group membership and identity, rites of passage, and other cultural aspects.”

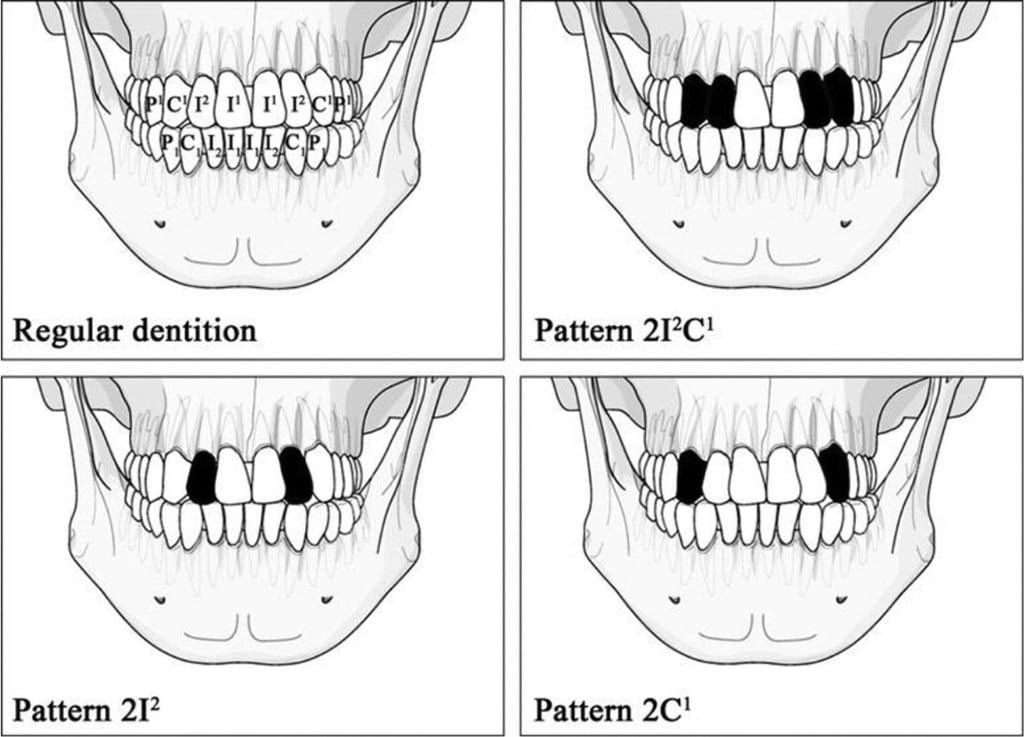

As the Austronesians migrated south, some communities maintained the tooth ablation culture while others did not. Additionally, some communities altered the practice by incorporating teeth blackening or filing.

Understanding why these cultural shifts occurred is complex, and traditions often change over several generations. But, the researchers said telling this story is an intriguing possibility for future research.